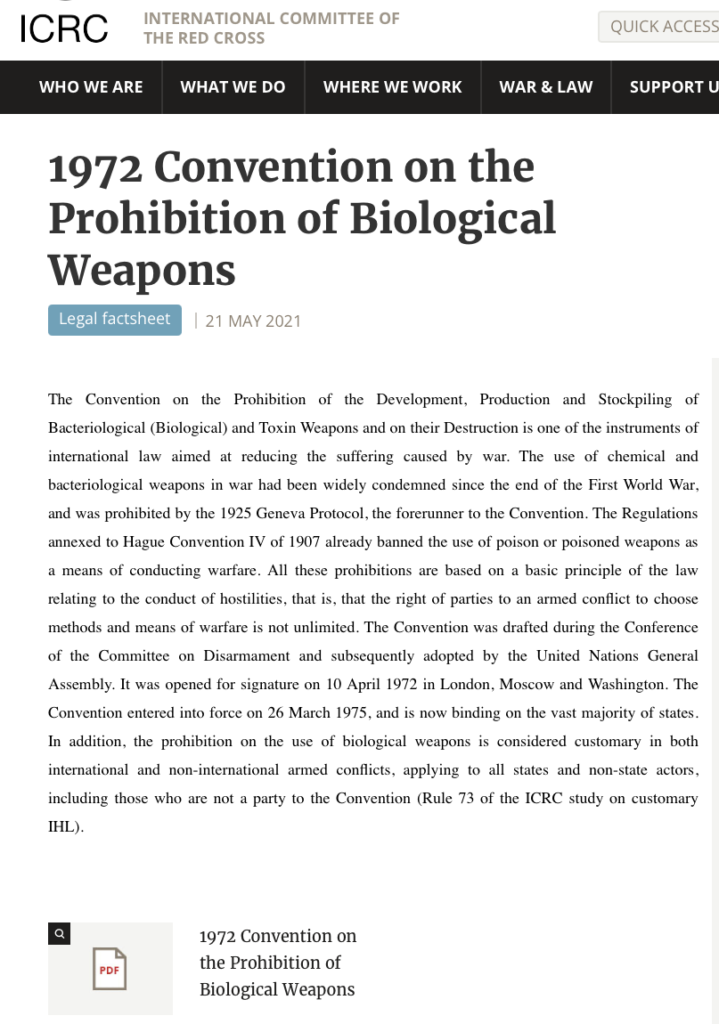

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) is an international treaty that prohibits the development, production, and possession of biological weapons. It was opened for signature in 1972 and entered into force in 1975. The BWC embodies the global community’s commitment to preventing the use of biological agents as weapons of war or terrorism.

Advancements in biotechnology have provided scientists with unprecedented capabilities to manipulate and engineer living organisms. While these discoveries offer countless grave risks when misused. Unfortunately, the lack of stringent regulations regarding bioweapons research has given rise to potentially dangerous experiments in laboratories across the globe.

In today’s world, where advancements in science and technology are at their peak, we must remain vigilant and aware of the potential dangers that may arise. One such threat that has been a cause for concern is the research and development of bioweapons. The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) was created to prohibit these activities, yet there seems to be a lack of effective monitoring and enforcement.

The Biological Weapons Convention aims to eliminate the threat posed by biological weapons. It was established in 1972 and now has 183 member states. The treaty prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and acquisition of biological weapons, as well as their transfer to other states or non-state actors.

In 1968, countries worldwide united to establish a complete prohibition on the creation, manufacture, and procurement of biological weapons. The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) was established due to the acknowledgment of the catastrophic consequences that bioweapons could inflict on humanity. Nevertheless, doubts emerge regarding the effectiveness of enforcing this global agreement. Is there anyone efficiently overseeing and deterring violations in bioweapons research? This article examines the present condition of supervision and investigates the potential dangers linked to unregulated bioweapons research.

Without rigorous oversight, there is a genuine risk that some countries or non-state actors may engage in secretive bioweapons research. Technological advancements, such as gene editing and synthetic biology, further complicate the detection of prohibited activities. Unauthorized bioweapons research could weaponize diseases, exploit vulnerabilities, and potentially cause widespread devastation.

The consequences of unchecked bioweapons research are vast. Violations of the ban undermine global security, create an imbalanced playing field, and erode trust between nations. The potential spread of lethal pathogens intentionally created in laboratories poses severe risks to human health, agricultural systems, and the environment. The international community needs to address these risks promptly and effectively.

The ban on bioweapons research through the Biological Weapons Convention is a critical step towards safeguarding humanity. However, current concerns regarding the lack of effective monitoring and verification mechanisms highlight the need for proactive measures to prevent violations.

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), or Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), is a disarmament treaty that effectively bans biological and toxin weapons by prohibiting their development, production, acquisition, transfer, stockpiling and use.

ICRC: 21 MAY 2021

1972 Convention on the Prohibition of Biological Weapons

Download pdf: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/1972-convention-prohibition-bacteriological-weapons-and-their-destruction-factsheet

Bioweapons research is banned by an international treaty – but nobody is checking for violations

Scientists are making dramatic progress with techniques for “gene splicing” – modifying the genetic makeup of organisms.

This work includes bioengineering pathogens for medical research, techniques that also can be used to create deadly biological weapons. It’s an overlap [a] that’s helped fuel speculation [b] that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus was bioengineered at China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology and that it subsequently “escaped” through a lab accident to produce the COVID-19 pandemic.

[a] Could gene editing tools such as CRISPR, be used as a biological weapon?https://theconversation.com/could-gene-editing-tools-such-as-crispr-be-used-as-a-biological-weapon-82187 [b] The origin of COVID: Did people or nature open Pandora’s box at Wuhan?https://thebulletin.org/2021/05/the-origin-of-covid-did-people-or-nature-open-pandoras-box-at-wuhanRelated Article:

The world already has a legal foundation [c] to prevent gene splicing for warfare: the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention [d]. Unfortunately, nations have been unable to agree on how to strengthen the treaty. Some countries [e] have also pursued bioweapons research and stockpiling in violation of it.

[c] https://dx.doi.org/10.1089%2Fhs.2017.0082 [d] https://www.un.org/disarmament/biological-weapons/ [e] https://fas.org/blogs/secrecy/2012/07/soviet_bw/As a member of President Bill Clinton’s National Security Council from 1996 to 2001, I had a firsthand view [f] of the failure to strengthen the convention. From 2009 to 2013, as President Barack Obama’s White House coordinator for weapons of mass destruction, I led a team that grappled [g] with the challenges of regulating potentially dangerous biological research in the absence of strong international rules and regulations.

[f] https://www.brandeis.edu/facultyguide/person.html?emplid=45b03f10247276eeaf30fadbc8afc2261b06795d [g] https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2011-05/pursuing-prague-agenda-interview-white-house-coordinator-gary-samoreThe history of the Biological Weapons Convention reveals the limits [h] of international attempts to control research and development of biological agents.

[h] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2017/09/06/the-biological-weapons-convention-at-a-crossroad/1960s-1970s: International negotiations to outlaw biowarfare

The United Kingdom first proposed [i] a global biological weapons ban [j] in 1968.

[i] https://doi.org/10.1177/0096340211407400 [j] https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/brandeis-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3300058Reasoning that bioweapons had no useful military or strategic purpose given the awesome power of nuclear weapons, the U.K. had ended its offensive bioweapons program [k] in 1956. But the risk remained that other countries might consider developing bioweapons as a poor man’s atomic bomb [l].

[j] http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C14396 [l] https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713509049In the original British proposal, countries would have to identify facilities and activities with potential bioweapons applications. They would also need to accept on-site inspections by an international agency to verify these facilities were being used for peaceful purposes.

These negotiations gained steam in 1969 when the Nixon administration ended [m] America’s offensive biological weapons program and supported the British proposal. In 1971, the Soviet Union announced its support [n] – but only with the verification provisions stripped out. Since it was essential to get the USSR on board, the U.S. and U.K. agreed to drop those requirements.

[m] https://www.jstor.org/stable/3092154 [n] https://legal.un.org/avl/ha/cpdpsbbtwd/cpdpsbbtwd.htmlIn 1972 the treaty was finalized. After gaining the required signatures, it took effect in 1975.

Under the convention [o] , 183 nations [p] have agreed not to “develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain” biological materials that could be used as weapons. They also agreed not to stockpile or develop any “means of delivery” for using them. The treaty allows “prophylactic, protective or other peaceful” research and development – including medical research.

[o] https://treaties.unoda.org/t/bwc [p] https://www.un.org/disarmament/biological-weapons/about/membership-and-regional-groupsHowever, the treaty lacks any mechanism to verify that countries are complying with these obligations.

1990s: Revelations of treaty violations

This absence of verification was exposed as the convention’s fundamental flaw [1] two decades later, when it turned out that the Soviets had a great deal to hide.

[1] https://thebulletin.org/2019/11/the-biological-weapons-convention-protocol-should-be-revisited/In 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin revealed the Soviet Union’s massive biological weapons program [2] . Some of the program’s reported experiments [3] involved making viruses and bacteria more lethal and resistant to treatment. The Soviets also [4]weaponized and mass-produced a number of dangerous naturally occurring viruses, including the anthrax and smallpox viruses, as well as the plague-causing Yersinia pestis bacterium.

[2] https://fas.org/blogs/secrecy/2012/07/soviet_bw/ [3] https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674045132-007 [4] https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674065260 [5] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-09-15-mn-859-story.htmlYeltsin in 1992 ordered the program’s end ( https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-09-15-mn-859-story.html) and the destruction of all its materials. But doubts remain ( https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/is-russia-violating-the-biological-weapons-convention/) whether this was fully carried out.

Another treaty violation [6] came to light after the U.S. defeat of Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War. United Nations inspectors discovered an Iraqi bioweapons stockpile [7], including 1,560 gallons (6,000 liters) of anthrax spores and 3,120 gallons (12,000 liters) of botulinum toxin. Both had been loaded into aerial bombs, rockets and missile warheads, although Iraq never used these weapons.

[6] https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/sciencenow/0401/02-hist-08.html [7] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9244334/In the mid-1990s, during South Africa’s transition to majority rule, evidence emerged of the former apartheid regime’s chemical and biological weapons program[8]. As revealed by the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the program [9] focused on assassination. Techniques included infecting cigarettes and chocolates with anthrax spores, sugar with salmonella and chocolates with botulinum toxin.

[8] https://unidir.org/publication/project-coast-apartheids-chemical-and-biological-warfare-programme [9] https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/plague/sa/In response to these revelations, as well as suspicions [10] that North Korea, Iran, Libya and Syria were also violating the treaty, the U.S. began urging other nations to close the verification gap. But despite 24 meetings over seven years, a specially formed group of international negotiators failed to reach agreement on how to do it [11]. The problems were both practical and political.

[10] https://doi.org/10.1017%2FS0002930000030098 [11] https://doi.org/10.1038/414675aMonitoring biological agents

Several factors make verification of the bioweapons treaty difficult.

First, the types of facilities that research and produce biological agents, such as vaccines [12], antibiotics, vitamins, biological pesticides[13] and certain foods [14], can also produce biological weapons. Some pathogens with legitimate medical and industrial uses can also be used for bioweapons.

[12] https://theconversation.com/3-medical-innovations-fueled-by-covid-19-that-will-outlast-the-pandemic-156464 [13] https://theconversation.com/can-random-bits-of-dna-lead-to-safe-new-antibiotics-and-herbicides-83550 [14] https://theconversation.com/moving-beyond-pro-con-debates-over-genetically-engineered-crops-59564

Further, large quantities of certain biological weapons can be produced quickly, by few personnel and in relatively small facilities. Hence, biological weapons programs are more difficult for international inspectors to detect than nuclear or chemical programs, which typically require large facilities, numerous personnel and years of operation.

So an effective bioweapons verification process would require nations to identify a large number of civilian facilities. Inspectors would need to monitor them regularly. The monitoring would need to be intrusive, allowing inspectors to demand “challenge inspections,” meaning access on short notice to both known and suspected facilities.

Finally, developing bioweapons defenses [15] – as permitted under the treaty – typically requires working with dangerous pathogens and toxins, and even delivery systems. So distinguishing legitimate biodefense programs [16] from illegal bioweapons activities often comes down to intent – and intent is hard to verify.

[15] https://warontherocks.com/2020/05/the-pandemic-and-americas-response-to-future-bioweapons/ [16] https://www.lawfareblog.com/enhancing-biological-weapons-defenseBecause of these inherent difficulties, verification faced stiff opposition.

Political opposition to bioweapons verification

As the White House official responsible for coordinating the U.S. negotiating position, I often heard concerns and objections from important government agencies.

The Pentagon expressed fears that inspections of biodefense installations would compromise national security or lead to false accusations of treaty violations. The Commerce Department opposed intrusive international inspections on behalf of the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. Such inspections might compromise trade secrets, officials contended, or interfere with medical research or industrial production.

Germany and Japan, which also have large pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, raised similar objections. China, Pakistan, Russia and others opposed nearly all on-site inspections. Since the rules under which the negotiation group operated required consensus, any single country could block agreement.

In January 1998, seeking to break the deadlock, the Clinton administration proposed [17] reduced verification requirements. Nations could limit their declarations to facilities “especially suitable” for bioweapons uses, such as vaccine production facilities. Random or routine inspections of these facilities would instead be “voluntary” visits or limited challenge inspections – but only if approved by the executive council of a to-be-created international agency monitoring the bioweapons treaty.

[17] https://fas.org/nuke/control/bwc/news/98022001_ppo.htmlBut even this failed to achieve consensus among the international negotiators.

Finally, in July 2001, the George W. Bush administration rejected the Clinton proposal [18] – ironically, on the grounds that it was not strong enough to detect cheating. With that, the negotiations collapsed [19].

[18] http://www.sussex.ac.uk/Units/spru/hsp/documents/cbwcb53-Pearson.pdf [19] https://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/08/world/conference-on-biological-weapons-breaks-down-over-divisions.htmlSince then, nations have made no serious effort to establish a verification system [20] for the Biological Weapons Convention.

[20] https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/09/world/09biowar.htmlEven with the amazing advances scientists have made in genetic engineering since the 1970s, there are few signs that countries are interested in taking up the problem again.

This is especially true in today’s climate of accusations against China, and China’s refusal to fully cooperate to determine the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additional Information:

Why the world banned chemical weapons

Yes, it’s because they’re morally hideous. But it’s also because they don’t work.

Ref: https://www.politico.eu/article/why-the-world-banned-chemical-weapons/

Source: ICRC, Wikipedia, The Conversation,

Also Read: