Probe finds 80 alleged sex abuse cases linked to WHO’s DRC work

Media briefing on Independent Commission's review of the allegations of sexual abuse & exploitation during the #Ebola 2018-2020 outbreak in #DRC https://t.co/1vce2FZcGQ

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) September 28, 2021

Internal emails reveal WHO knew of sex abuse claims in Congo

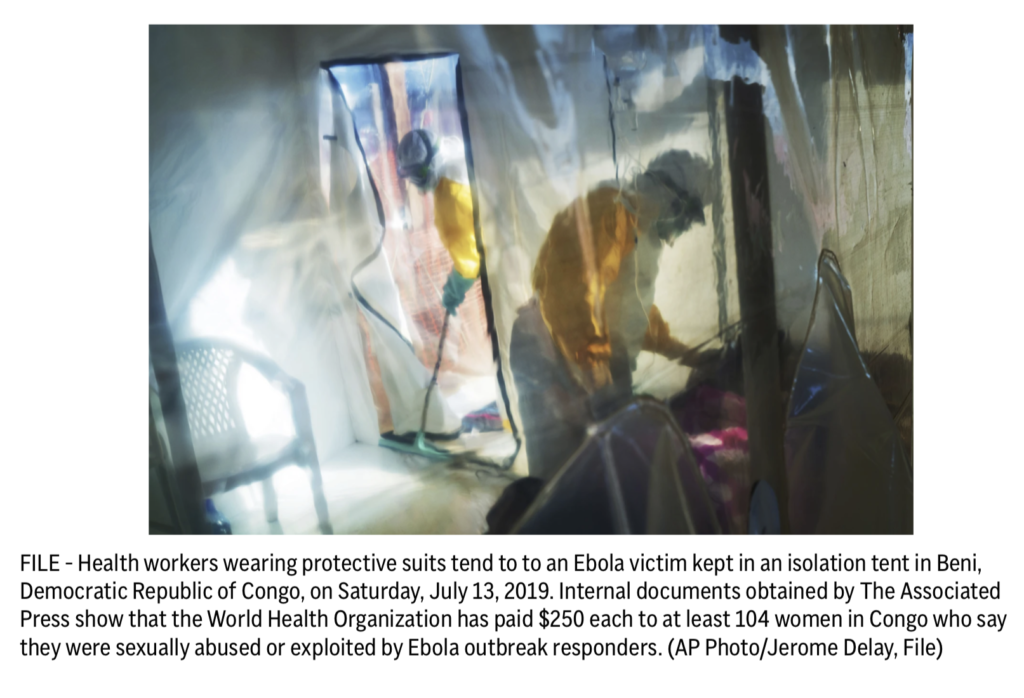

12th May 2021: The revelations come at a time when the UN health agency is winding down its response to two recent Ebola epidemics in Congo and Guinea.

When Shekinah was working as a nurse’s aide in northeastern Congo in January 2019, she said, a World Health Organization doctor offered her a job investigating Ebola cases at double her previous salary – with a catch.

“When he asked me to sleep with him, given the financial difficulties of my family. I accepted,” said Shekinah (25), who asked that only her first name be used for fear of repercussions. She added that the doctor, Boubacar Diallo, who often bragged about his connections to WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, also offered several of her friends jobs in return for sex.

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL STORY A WHO staffer and three Ebola experts working in Congo during the outbreak separately told management about general sex abuse concerns around Diallo, The Associated Press has learned. They said they were told not to take the matter further. WHO has been facing widespread public allegations of systemic abuse of women by unnamed staffers, to which Tedros declared outrage and emergencies director Dr. Michael Ryan said, “We have no more information than you have.” But an AP investigation has now found that despite its public denial of knowledge, senior WHO management was not only informed of alleged sexual misconduct in 2019 but was asked how to handle it. The AP has also for the first time tracked down the names of two doctors accused of sexual misconduct, Diallo and Dr. Jean-Paul Ngandu, both of whom were reported to WHO. Ngandu was accused by a young woman of impregnating her. In a notarized contract obtained by the AP, two WHO staffers, including a manager, signed as witnesses to an agreement for Ngandu to pay the young woman, cover her health costs and buy her land. “The deal was made ‘to protect the integrity and reputation’ of WHO,” Ngandu said. When contacted, both Diallo and Ngandu denied any wrongdoing. The investigation was based on interviews with dozens of WHO staffers, Ebola officials in Congo, private emails, legal documents and recordings of internal meetings as obtained. A senior manager, Dr. Michel Yao, received emailed complaints about both men. Yao didn’t fire Ngandu despite the reported misconduct. Yao didn’t have the power to terminate Diallo, a Canadian, who was on a different kind of contract, but neither he nor any other WHO managers put Diallo on administrative leave. The AP was unable to ascertain whether Yao forwarded either complaint to his superiors or the agency’s internal investigators, as required by WHO protocol. Yao has since been promoted to be director of Geneva’s Strategic Health Operations Department. Eight top officials privately acknowledged that WHO had failed to effectively tackle sexual exploitation during the Ebola outbreak and that the problem was systemic, recordings of internal meetings show. The revelations come at a time when the UN health agency is winding down its response to two recent Ebola epidemics in Congo and Guinea, and is already under pressure for its management of the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. WHO declined to comment on specific sex abuse allegations, and none of the 12 WHO officials contacted responded to repeated requests for comment. Spokeswoman Marcia Poole noted that Tedros announced an independent investigation of sex abuse in Congo after media reports came out in October. Findings are due at earliest in August, investigators have said. “Once we have these, we will review them carefully and take appropriate additional actions. We are aware that more work is needed to achieve our vision of emergency operations that serve the vulnerable while protecting them from all forms of abuse,” Poole said. WHO’s code of conduct for staffers says they are “never to engage in acts of sexual exploitation” and to “avoid any action that could be perceived as an abuse of privileges”, reflecting the unequal power dynamic between visiting doctors and economically vulnerable women. But an internal WHO audit last year found some aid workers weren’t required to complete the agency’s training on sex abuse prevention before starting work during Ebola. “All of us may have been suspecting for as long as the Ebola response was taking (place) that something like this would be possible,” said Andreas Mlitzke, director of WHO’s office of Compliance, Risk Management, and ethics, during an internal meeting in November. Mlitzke likened WHO officials in Congo to “an invading force” and said, “Things like this have historically happened in wartime.” Mlitzke said during the meeting that WHO typically “takes the passive approach” in its investigations, and that it couldn’t be expected to uncover wrongdoing among staffers. “What prevents us from doing something proactive is our own psychology,” he said. Meanwhile, Ryan said that the sexual harassment incidents were unlikely to be exceptional. “You can’t just pin this and say you have one field operation that went badly wrong. It does reflect a culture as well – This is in some sense the tip of an iceberg,” he told his colleagues in an internal meeting. Internal emails from November 2019 show WHO directors were alarmed enough by the abuse complaints that they drafted a strategy to prevent sexual exploitation and appointed two “focal points” to liaise with colleagues in Congo and elsewhere. Directors also ordered confidential probes into sexual abuse problems more broadly and UN training on how to prevent sexual harassment, along with the independent investigation announced last year. 11 January 2023: Internal documents obtained by the Associated Press show the World Health Organization knew of past sexual misconduct charges involving one of its staffers _ who was also accused in a similar incident at a Berlin conference in October When a doctor tweeted that she was “sexually assaulted” by a World Health Organization staffer at a Berlin conference in October, the U.N. agency’s director-general assured her that WHO had “zero tolerance” for misconduct. Internal documents obtained by The Associated Press show the same WHO staffer, Fijian physician Temo Waqanivalu, was previously accused of similar sexual misconduct in 2018. CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL STORY A former WHO ombudsman who helped assess the previous allegation against Waqanivalu said the agency had missed a chance to root out bad behavior. “I felt extremely angry and guilty that the dysfunctional (WHO) justice system has led to another assault that could have been prevented,” said the staffer, who spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity for fear of losing their job. The previous allegation didn’t derail Waqanivalu’s career at WHO. As the new accusation surfaced, he was seeking to become WHO’s top official in the western Pacific with high-level support, documents show. In the coming weeks, the agency’s highest governing body is meeting to set public health priorities and may discuss how and when the election for the region’s next director might occur. Waqanivalu hung up when the AP contacted him for comment. He “categorically” denied that he had ever sexually assaulted anyone, including at the Berlin conference, according to correspondence between him and WHO investigators that the AP obtained. WHO said its report into the Berlin conference complaint “is in its final stage” and would soon be submitted to Tedros. The claims against Waqanivalu are the latest in a series of misconduct accusations at WHO. The agency’s last regional director in the western Pacific was put on leave in August, months after AP reported that staffers had accused him of abusive behavior that compromised the U.N. agency’s response to COVID-19. ___ The earlier accusation against Waqanivalu came after a 2017 workshop in Japan, where a WHO employee said Waqanivalu had harassed her at a post-work dinner. “Under the table, (Waqanivalu) took off his shoes, lifted one of his legs and toe(s) between my legs,” the woman wrote in a 2018 report that was shared with senior WHO officials. She left the restaurant and said Waqanivalu followed her. After she said goodbye, Waqanivalu “proceeded to give me a hug, grabbing my buttocks with both of his hands and trying to kiss my lips,” the woman said. The AP does not typically name people who say they have been sexually harassed unless they come forward publicly. After submitting her confidential report to WHO in July 2018, the case was “tossed around in (Geneva) for months,” one of the ombudsmen wrote to the woman in an email. The woman was later informed that Waqanivalu would be given an “informal warning” and that the case was considered closed. She wrote in an email to a WHO ombudsman that the agency’s ethics office told her that pressing for an investigation might not be her best option. In October, Waqanivalu sat on a panel at the World Health Summit in Berlin as part of a high-level conference with attendees including WHO chief Tedros. In a hotel lobby one evening, numerous people were having drinks, including Waqanivalu and Dr. Rosie James, a young British-Canadian physician and former consultant for WHO. “We were talking about his work at WHO and he just started putting his hand on my bottom and keeping it there,” James told the AP. James said Waqanivalu “firmly held my buttock in his hand multiple times (and) pressed his groin” into her. Before Waqanivalu left, she says he repeatedly asked for her hotel room. Later that night, she tweeted about the encounter, prompting WHO chief Tedros to pledge to do “everything we can to help you.” James said WHO investigators interviewed her, but that Tedros never followed up. WHO offered to pay for any private therapy costs linked to the incident, James said. In Waqanivalu’s interview with WHO investigators, he said he greeted James “by tapping her on her left upper arm,” according to a record of the discussion obtained by AP. He acknowledged asking for her hotel room number, saying he made the request “to connect, if need be.” Waqanivalu told investigators he believed people in the group, including James, “were under the influence of alcohol.” Last fall, Waqanivalu, who oversees a small team in non-communicable diseases at WHO’s headquarters, put himself forward as a candidate to be WHO’s next director for the western Pacific. “The experience and expertise I have gathered over the years … have given me the relevant credentials,” Waqanivalu wrote in a September letter to Fiji’s then-Prime Minister. About a week after the Berlin conference, the chair of WHO’s top governing body in the region told Waqanivalu in a message seen by the AP that his name was mentioned “as a potential candidate” to be the next regional director. “That would be an opportunity for you, Dr. Temo,” Waqanivalu was told. A memo from the prime minister’s office dated Oct. 17 confirmed “Fiji’s proposed candidacy” of Waqanivalu to the position. A WHO-produced election-style campaign brochure created in September outlined Waqanivalu’s vision. “Under my leadership, WHO will empower people to serve within their countries,” the document reads. Paula Donovan, co-director of the Code Blue campaign, which seeks to hold U.N. personnel accountable for sexual offenses, said the allegations regarding Waqanivalu were deeply worrying. She said it was particularly concerning that an official accused of sexual harassment had been potentially in line for such a prominent leadership role and that WHO had failed to uphold its own “zero tolerance” policy for unprofessional behavior. “It’s patently false that WHO does not condone sexual misconduct,” Donovan said, calling for its member countries to overhaul the agency’s internal structures so that its officials are held accountable. “When WHO keeps this kind of stuff under wraps, they are giving sexual predators carte blanche to do it again with impunity.” CLICK HERE Earlier this year, the doctor who leads the World Health Organization’s efforts to prevent sexual abuse travelled to Congo to address the biggest known sex scandal in the U.N. health agency’s history, the abuse of well over 100 local women by staffers and others during a deadly Ebola outbreak. According to an internal WHO report from Dr. Gaya Gamhewage’s trip in March, one of the abused women she met gave birth to a baby with “a malformation that required special medical treatment,” meaning even more costs for the young mother in one of the world’s poorest countries. To help victims like her, the WHO has paid $250 each to at least 104 women in Congo who say they were sexually abused or exploited by officials working to stop Ebola. That amount per victim is less than a single day’s expenses for some U.N. officials working in the Congolese capital — and $19 more than what Gamhewage received per day during her three-day visit — according to internal documents obtained by The Associated Press. The amount covers typical living expenses for less than four months in a country where, the WHO documents noted, many people survive on less than $2.15 a day. The payments to women didn’t come freely. To receive the cash, they were required to complete training courses intended to help them start “income-generating activities.” The payments appear to try to circumvent the U.N.’s stated policy that it doesn’t pay reparations by including the money in what it calls a “complete package” of support. Many Congolese women who were sexually abused have still received nothing. WHO said in a confidential document last month that about a third of the known victims were “impossible to locate.” The WHO said nearly a dozen women declined its offer. The total of $26,000 that WHO has provided to the victims equals about 1% of the $2 million, WHO-created “survivor assistance fund” for victims of sexual misconduct, primarily in Congo. In interviews, recipients told the AP the money they received was hardly enough, but they wanted justice even more. Paula Donovan, who co-directs the Code Blue campaign to eliminate what it calls impunity for sexual misconduct in the U.N., described the WHO payments to victims of sexual abuse and exploitation as “perverse.” “It’s not unheard of for the U.N. to give people seed money so they can boost their livelihoods, but to mesh that with compensation for a sexual assault, or a crime that results in the birth of a baby, is unthinkable,” she said. Requiring the women to attend training before receiving the cash set uncomfortable conditions for victims of wrongdoing seeking help, Donovan added. The two women who met with Gamhewage told her that what they most wanted was for the “perpetrators to be brought to account so they could not harm anyone else,” the WHO documents said. The women were not named. “There is nothing we can do to make up for (sexual abuse and exploitation),” Gamhewage told the AP in an interview. The WHO told the AP that criteria to determine its “victim survivor package” included the cost of food in Congo and “global guidance on not dispensing more cash than what would be reasonable for the community, in order to not expose recipients to further harm.” Gamhewage said the WHO was following recommendations set by experts at local charities and other U.N. agencies. “Obviously, we haven’t done enough,” Gamhewage said. She added the WHO would ask survivors directly what further support they wanted. Source: The New Indian Express, Independent, AP, Aljazeera Also Read:WHO knew of past sex misconduct claims against doctor

Internal documents show the World Health Organization paid sexual abuse victims in Congo $250 each