In a world where nearly every action, every transaction, and every conversation is digitally recorded, do you really have the right to privacy? Or is your personal life just another open book, vulnerable to anyone who chooses to read it? What if I told you that in India, this very question became the battleground for one of the most critical legal cases of our time—one historic case where the stakes were nothing less than our right to live privately, unseen and untouched by constant scrutiny. This is the story of Justice KS Puttaswamy versus the Union of India. The landmark 2017 judgment declared the right to privacy a fundamental right under the Indian Constitution. This case didn’t just defend privacy; it redefined freedom for over a billion people. This isn’t just a legal battle—it’s a story about you, about me, about all of us, and the choices we have over our own lives in an increasingly digital world. So stay with me, because by the end of this article, you might just question what privacy truly means.

The 2017 Supreme Court judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India revolutionized India’s constitutional framework by recognizing the right to privacy as an intrinsic part of the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution. By overturning colonial-era precedents like M.P. Sharma v. Satish Chandra (1954) and Kharak Singh v. State of U.P. (1962), the Court redefined privacy as a cornerstone of human dignity, autonomy, and informational self-determination. This landmark ruling not only catalyzed India’s first comprehensive data protection law- the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA), 2023- but also reshaped digital rights in an era dominated by artificial intelligence, mass surveillance, and algorithmic governance.

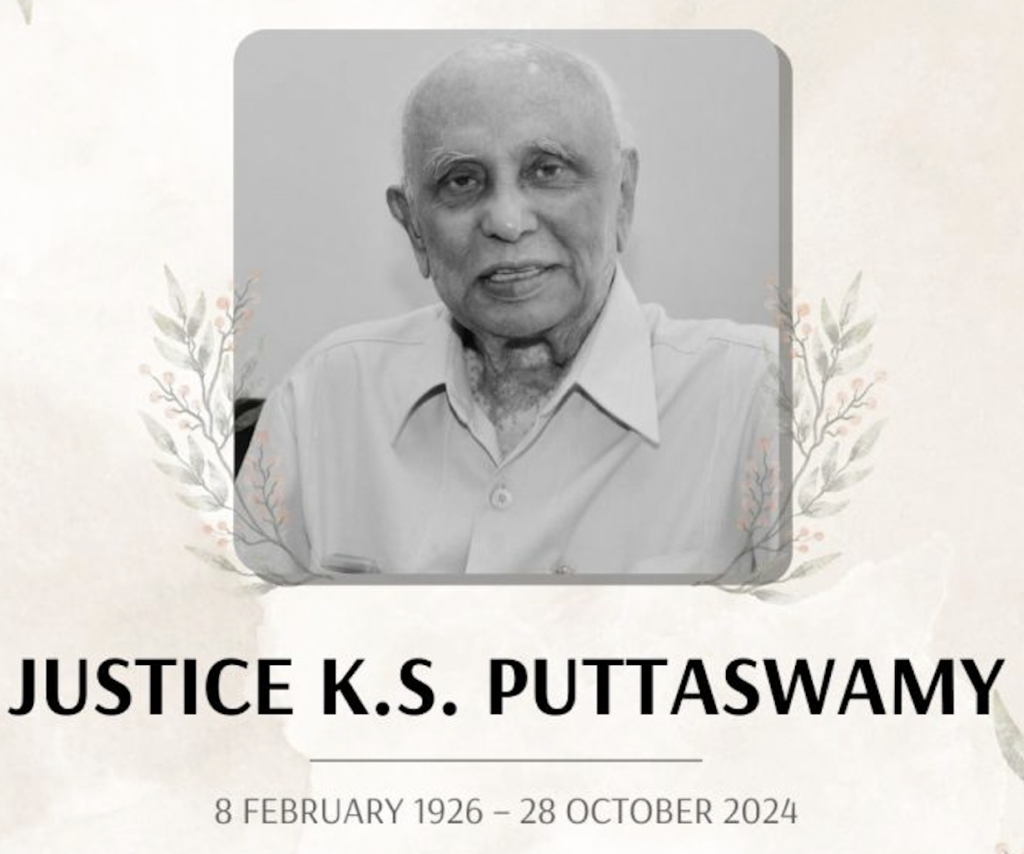

Justice K S Puttaswamy, former Karnataka High Court judge and the lead petitioner in the seminal ‘right to privacy case’, passed away, at the age of 98. Justice Puttaswamy, who was born in 1926 near Bengaluru, enrolled as an advocate in 1952 after studying at Maharaja College in Mysuru and the Government Law College in Bengaluru. He practised at the Mysore High Court before it came to be known as the Karnataka High Court and would go on to become an Additional Government Advocate before being appointed as a judge of the Karnataka High Court on November 28, 1977.

The State of Privacy in India Before the Puttaswamy Judgment

Before 2017, India lacked a comprehensive data privacy law. The Information Technology (IT) Act, 2000, and its amendments provided some safeguards, but these were fragmented and inadequate. Sensitive data, especially in healthcare, was often mishandled, leading to breaches and loss of public trust.

For instance, the Aadhaar data breach in 2018 exposed the personal information of millions, highlighting the vulnerabilities in India’s data protection mechanisms. Healthcare organizations, which handle highly sensitive patient data, were particularly at risk. Without clear guidelines, hospitals, clinics, and digital health platforms struggled to protect patient confidentiality, leading to instances of data misuse and unauthorized access.

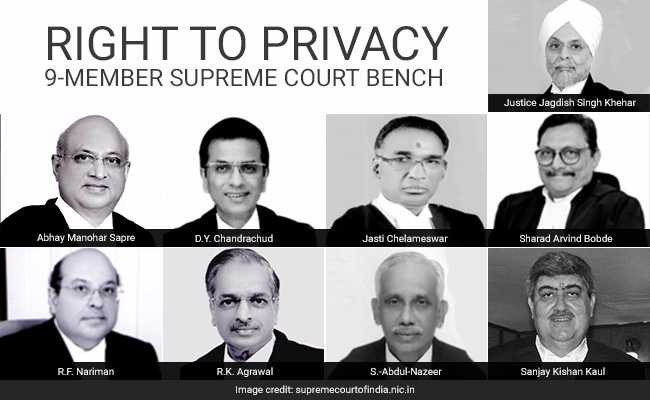

The Bench and Legal Representation

The case was heard by a nine-judge bench, comprising:

- Chief Justice J.S. Khehar

- Justice D.Y. Chandrachud

- Justice Abdul Nazeer

- Justice Rohinton Nariman

- Justice S.K. Kaul

- Justice Sharad Bobde

- Justice Jasti Chelameswar

- Justice Abhay Sapre

- Justice A.K. Sikri

The petitioners in the case included Justice K.S. Puttaswamy and several civil society activists, represented by prominent lawyers such as Shyam Divan, Kapil Sibal, Gopal Subramanium, K.V. Vishwanathan, and Meenakshi Arora. The respondents included the Union of India and several states, represented by Attorney General K.K. Venugopal and other government lawyers.

The Puttaswamy Judgment: A Turning Point

The Puttaswamy judgment was a watershed moment for data privacy in India. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision recognized privacy as a fundamental right, stating that “the right to privacy is intrinsic to the right to life and personal liberty.” The judgment emphasized the need for a robust data protection framework and introduced key principles such as:

- Informed Consent: Individuals must be fully aware of how their data is being used.

- Data Minimization: Only the necessary amount of data should be collected and processed.

- Purpose Limitation: Data should be used only for the purpose for which it was collected.

For healthcare, these principles were revolutionary. Patient data, which includes medical histories, treatment records, and biometric information, was now recognized as deserving of the highest level of protection. The judgment also highlighted the need for sector-specific regulations, particularly for healthcare, where data breaches can have life-altering consequences.

Use of Legal Jargon

- Fundamental Right

- Rights enshrined in Part III of the Constitution (e.g., equality, free speech, life) that are enforceable against the state. Puttaswamy elevated privacy to this status, ensuring it is protected as a non-negotiable constitutional safeguard.

- Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty)

- A constitutional guarantee that prohibits the deprivation of life or liberty except through a fair legal procedure. The Court expanded its scope to include privacy, dignity, and informational autonomy, recognizing that privacy is essential for meaningful human existence.

- Proportionality Test

- A legal principle requiring state actions that infringe on fundamental rights (e.g., surveillance, data collection) to be necessary, rational, and the least restrictive means to achieve a legitimate state aim. This framework now governs all privacy-related state interventions.

- Judicial Precedent

- Past court decisions that guide future rulings. Puttaswamy explicitly overruled M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh, which had denied privacy as a separate right, and aligned Indian law with international standards such as the EU’s GDPR and the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

- Informational Privacy

- The protection of personal data from unauthorized collection, use, or disclosure. The Court emphasized this facet of privacy as critical in the digital age, directly influencing India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA), 2023, which mandates consent-based data processing and penalties for breaches.

Facts of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v Union of India

The case originally arose out of the challenge to the Aadhaar scheme, which was introduced by the UPA government in 2009. The scheme aimed to provide a unique identification number to every Indian resident, which would be linked to biometric data, including fingerprints and iris scans. Over time, concerns arose regarding the potential misuse of this vast amount of personal data. These concerns became more prominent when it was revealed that the data could be shared with various private entities, raising questions about the right to privacy of individuals.

The Proof

Background of the Case

K.S. Puttaswamy, a retired High Court judge, filed a petition in 2012 challenging the constitutionality of the Aadhaar program, in which the biometric identification program mandated the collection of personal data (fingerprints, iris scans) for accessing welfare benefits The government defended Aadhaar by arguing that privacy was not a fundamental right, relying on the 1954 M.P. Sharma ruling (which permitted warrantless searches under colonial-era laws) and the 1962 Kharak Singh decision (which upheld invasive police surveillance as constitutional).

To determine if privacy is a fundamental right, a three-judge bench referred the case to a nine-judge Constitutional Bench. This referral was critical, as earlier precedents had created legal ambiguity, leaving citizens vulnerable to unchecked state and corporate surveillance.

Key Issues Before the Court

- Does the Indian Constitution guarantee the right to privacy?

- Do the precedents set by M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh remain valid?

The Judgment: A Constitutional Renaissance

In a landmark unanimous decision on August 24, 2017, the Supreme Court ruled that privacy is a fundamental right guaranteed by Articles 21, 14, and 19. The judgment established three foundational principles:

- Human Dignity and Autonomy: Privacy safeguards an individual’s autonomy over personal choices, including marriage, sexual orientation, and reproductive rights. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud stated that “Privacy is the constitutional core of human dignity.”

- Informational Self-Determination: Individuals have the right to control their digital footprint. The Court stressed that data exploitation by states or corporations without consent violates constitutional morality.

- Proportionality and Legality: Any state intrusion into privacy must satisfy a four-pronged test:

- Legitimate aim (e.g., national security),

- Rational connection between means and ends,

- Necessity (least restrictive alternative),

- Balancing of public interest and individual harm.

Impact on Digital Rights and Governance

- Data Protection Laws:

The judgment prompted the enactment of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA), 2023, which:- Mandates consent for data collection,

- Penalizes breaches with fines up to ₹250 crore,

- Establishes a Data Protection Board for enforcement.

However,the DPDPA’s exemptions for government agencies, according to critics, compromise its effectiveness. For instance, the National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID), a counterterrorism database, operates without transparency, raising concerns about mass surveillance.

- Surveillance Reforms:

Courts now rigorously scrutinize state surveillance programs. For instance, in the Pegasus spyware scandal (2021), the Supreme Court formed an expert committee to investigate allegations of illegal surveillance, citing Puttaswamy’s proportionality test. The committee’s findings revealed that over 300 Indian citizens, including journalists and activists, were targeted, prompting calls for stricter oversight of intelligence agencies. - LGBTQ+ Rights:

By linking privacy to sexual autonomy, Puttaswamy paved the way for the decriminalization of same-sex relationships in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018). The Court held that “sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy.” This precedent has since been invoked in cases advocating for marriage equality and anti-discrimination laws. - Algorithmic Accountability:

The ruling has been used to challenge bias in AI systems. For example, in Rakshak Foundation v. Union of India (2023), petitioners argued that facial recognition systems used by police disproportionately target marginalized communities, violating their privacy. The Delhi High Court directed the government to conduct algorithmic audits to ensure compliance with Puttaswamy’s principles. - Global Influence:

Puttaswamy has inspired privacy reforms across South Asia. In 2022, Nepal’s Supreme Court cited the decision when it overturned a biometric voter registration scheme, and Sri Lanka’s draft data protection law is similar to the DPDPA’s consent-based framework.

Case Laws

1. M.P. Sharma v. Satish Chandra (1954)

- Holding: According to an eight-judge panel, the Indian Evidence Act allows for warrantless searches since the Constitution does not recognise privacy as a fundamental right.

- Puttaswamy’s Rejection: The Court called M.P. Sharma “overbroad,” emphasizing that fundamental rights must evolve with societal values. Justice S.K. Kaul noted, “Privacy cannot be sacrificed at the altar of state expediency.”

2. Kharak Singh v. State of U.P. (1962)

- Holding: Upheld police surveillance measures, including midnight domiciliary visits, as constitutional.

- Puttaswamy’s Rejection: Declared the decision “flawed,” affirming that privacy is a check on state power. Justice Rohinton Nariman stated, “Surveillance is a colonial relic incompatible with a free society.”

3. Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015)

- Holding: Struck down Section 66A of the IT Act, which criminalized “offensive” online speech, for violating free expression.

- Synergy with Puttaswamy: Both judgments prioritize individual autonomy in digital spaces. While Shreya Singhal protects free speech, Puttaswamy ensures that such speech is not chilled by surveillance.

4. Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018)

- Holding: Consensual same-sex relationships are no longer illegal under Section 377 of the IPC.

- Link to Puttaswamy: The Court cited privacy as central to sexual autonomy, stating, “Intimacy requires a zone of privacy free from state intrusion.”

Critical Viewpoint

Strengths

- Theoretical Robustness: Puttaswamy’s integration of dignity, autonomy, and equality provides a holistic framework for evaluating privacy infringements.

- Catalyst for Legislation: The judgment spurred the DPDPA, 2023, India’s first comprehensive data law.

Weaknesses

- Legislative Ambiguity:

The DPDPA exempts government agencies from consent requirements, enabling programs like the National Health Stack, which aggregates medical data without individual permission. - Judicial Inconsistency:

Post-Puttaswamy rulings like Romila Thapar v. Union of India (2018) (upholding state surveillance of activists) contradict the proportionality test, revealing a judiciary torn between liberty and security. - Corporate Accountability:

While Puttaswamy binds private entities, enforcement against tech giants like Meta remains lax. India’s 600 million social media users face rampant data exploitation without meaningful recourse.

Comparative Critique

Unlike the EU’s GDPR, which imposes strict penalties for data breaches (up to 4% of global turnover), India’s DPDPA caps fines at ₹250 crore (~$30 million)—a negligible sum for multinational corporations. This reflects a legislative prioritization of economic growth over privacy.

The Puttaswamy judgment redefined India’s constitutional ethos, but challenges persist:

- Legislative Gaps: The DPDPA exempts government agencies from key obligations, enabling mass surveillance programs like the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network System (CCTNS).

- Judicial Vigilance: Courts must rigorously apply the proportionality test to emerging technologies, such as facial recognition and predictive policing algorithms, which disproportionately target marginalized groups.

- Global Leadership: By aligning with the EU’s GDPR, Puttaswamy positions India as a leader in transnational privacy advocacy, influencing global debates on AI ethics and data justice.

Just as defamation law has adapted to protect online reputations, Puttaswamy underscores that privacy is not static. It demands perpetual evolution to counter algorithmic harm, data commodification, and state surveillance, ensuring India’s digital democracy remains rooted in dignity and autonomy.

In detail:

Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v Union of India Judgement

On August 24, 2017, the nine-judge bench delivered its unanimous judgement, which recognised the right to privacy as a fundamental right under the Indian Constitution. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, delivering the majority opinion, held that the right to privacy is protected under Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty) and is an essential aspect of the freedoms guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution.

The court overruled the earlier decisions in M.P. Sharma v. Satish Chandra and Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh, both of which had denied privacy as a fundamental right. The judgement clarified that privacy is integral to the dignity and autonomy of individuals and cannot be compromised without adequate justification. The court established that any encroachment on the right to privacy must meet the following three conditions:

- Legality: There must be a law that authorises the invasion of privacy.

- Necessity: The state must have a legitimate aim to justify the infringement.

- Proportionality: The means used to achieve the aim must be proportional to the infringement.

The judgement also emphasised that privacy extends to all spheres of life, including personal, familial, and sexual orientation. It underscored that sexual orientation is a core aspect of an individual’s privacy, and any discrimination based on it violates the right to dignity and equality under Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution.

Impact on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

One of the most notable aspects of the Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v Union of India decision was its direct impact on issues related to sexual orientation and gender identity. The Supreme Court held that discrimination against individuals based on sexual orientation is deeply offensive to their dignity and self-worth. The court recognised that sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy and that every individual has the right to decide their sexual preferences without interference from the state.

This part of the judgement laid the groundwork for the eventual decriminalisation of homosexuality in India through the Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018) case, where the Supreme Court struck down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalised consensual homosexual acts between adults.

The ADM Jabalpur Case Overruled

The Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v Union of India judgement also took a bold step in overruling the ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla (1976) case. In ADM Jabalpur, the Supreme Court had ruled that during a state of emergency, the right to life and personal liberty could be suspended. The Puttaswamy judgement reaffirmed the sanctity of the right to life, declaring that it is inalienable and cannot be suspended even during an emergency.

The judgement reminded the government that the right to life and personal liberty exists independently of the Constitution and is an inherent natural right. The court firmly rejected any notion that these rights could be overridden by the executive or the legislature.

Aftermath and Implications

The Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v Union of India case has had profound implications for several key issues in Indian law and society. The recognition of privacy as a fundamental right paved the way for greater protection of personal data and digital rights. It also strengthened individual autonomy, particularly in areas such as sexual orientation, marriage, and reproductive rights.

In addition to the Navtej Singh Johar decision, the judgement also played a crucial role in the Joseph Shine v. Union of India (2018) case, where the Supreme Court decriminalised adultery, further affirming the protection of privacy in personal relationships.

The case has been cited in numerous subsequent rulings, ensuring that privacy remains a critical part of the discourse on fundamental rights in India. It also triggered debates on the regulation of technology, especially in the context of data protection and privacy laws.

Justice K.S. Puttaswamy Judgment: The Foundation of India’s Data Privacy Revolution and Its Impact on Healthcare

From Puttaswamy to DPDP Act: What Changed?

The Puttaswamy judgment set the stage for the DPDP Act, which aims to codify the principles of data protection into law. However, while the Act aligns with some aspects of the judgment, there are notable gaps:

Alignment with Puttaswamy Principles:

- Consent: The DPDP Act mandates explicit consent for data processing, echoing the Puttaswamy judgment’s emphasis on informed consent.

- Data Minimization: The Act restricts data collection to what is necessary, aligning with the judgment’s principles.

- Right to Erasure: Individuals can request the deletion of their data, a direct reflection of the judgment’s focus on individual rights.

Gaps and Changes:

- No Explicit Right to Privacy: While Puttaswamy recognized privacy as a fundamental right, the DPDP Act focuses more on data protection, leaving broader privacy concerns unaddressed.

- Limited Scope: The Act applies only to digital data, excluding non-digital and anonymized data, which were highlighted in Puttaswamy.

- Healthcare-Specific Provisions: The DPDP Act lacks detailed guidelines for healthcare data, unlike GDPR’s health data-specific rules.

For healthcare stakeholders, these gaps pose challenges. For example, while the Act mandates consent for data processing, it does not provide clear guidelines on how healthcare providers should handle sensitive patient data in emergencies or research scenarios.

The Puttaswamy judgment has laid the foundation for a robust data privacy framework in India, with significant implications for the healthcare sector.

Some key takeaways from the Puttaswamy judgment and its impact on healthcare include:

- The need for a comprehensive data protection framework that addresses the unique challenges of the healthcare sector.

- The importance of balancing individual privacy rights with the need for data-driven healthcare innovations.

- The requirement for healthcare organizations to prioritize data protection and patient confidentiality.

Source: Linkedin, Lawful Legal, Law Bhoomi, Youtube

Also read: